Inhaltsverzeichnis

aufklappen

-

Title and Authorship

- Locations of the First Edition

- Author

- Contents

- Context and Classification

- Reception and Influence

- Bibliography

1. Title and Authorship![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

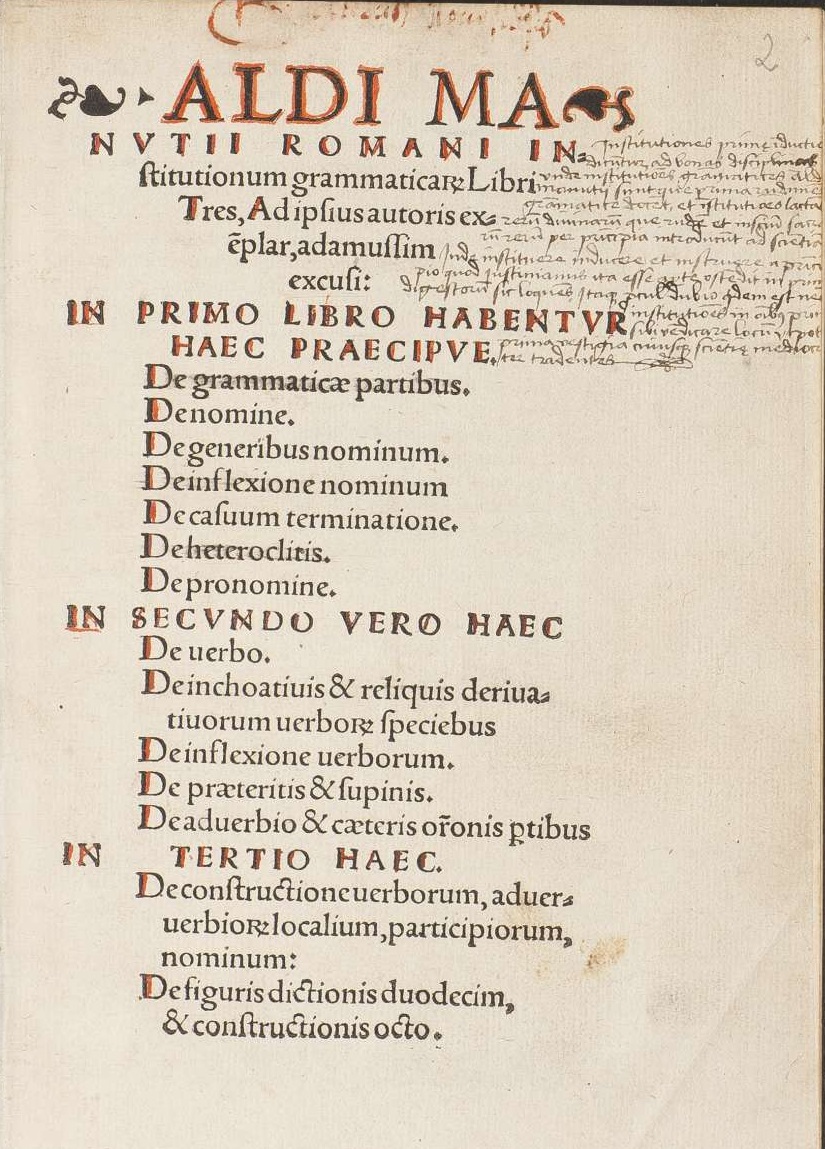

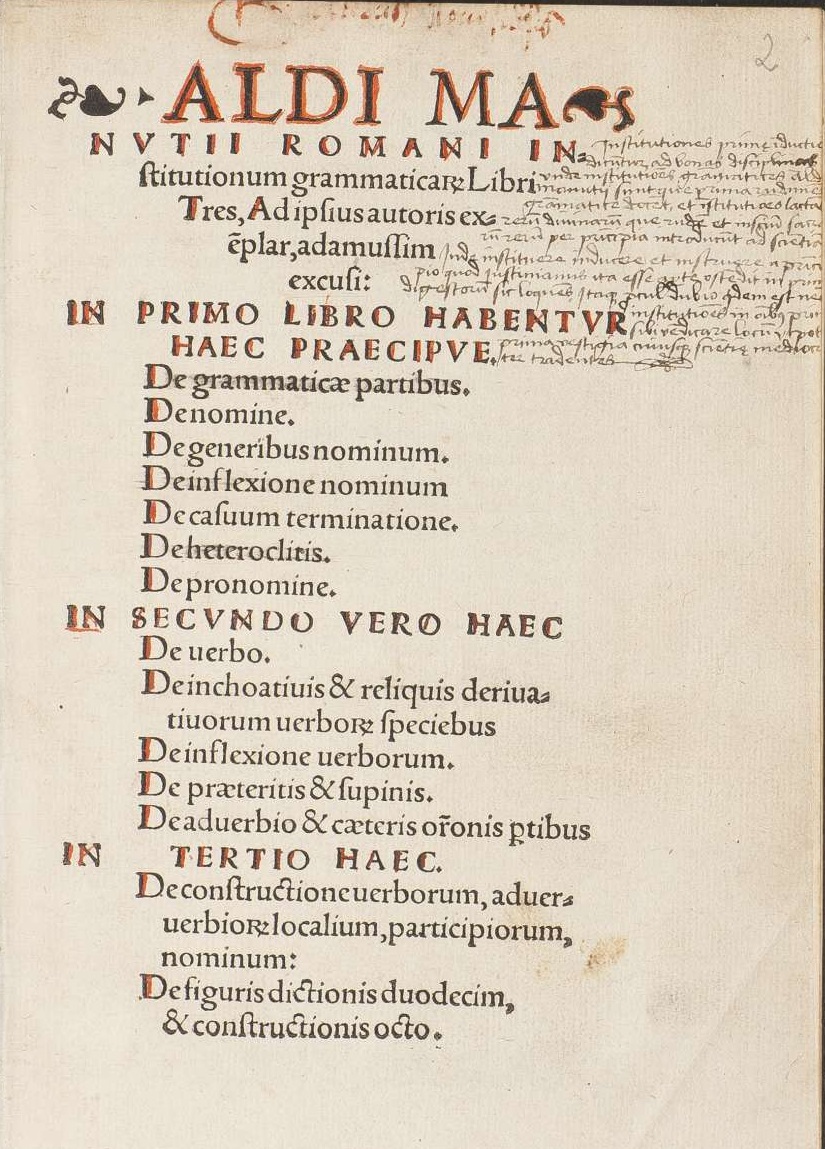

The famous Venetian printer Aldus Manutius wrote a Latin grammar, the earliest version of which is no longer extant; it was mentioned by him in a letter to Catarina Pio, dated March 14, 1487 (Pastorello 1957: 160-161). The earliest extant version of Aldus' grammar is the one published on March 9, 1493 by the Venetian publisher Andrea Torresani of Asola (Scarafoni 1947: 193-203; Jensen 1998: 237). The first edition from Aldus' own press published in 1501 was entitled Rudimenta Grammatices Latinae Linguae, followed by two other editions in quarto with additions and minor alterations, one in 1508 and the other during Aldus' lifetime in 1514. From the 1508 edition on, the compendium was generally entitled (Aldi Manutii Romani) Institutionum grammaticarum libri quatuor. He justified this title, reminiscent of Priscian's Institutiones grammaticae (’Principles of Grammar’) and Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria (’Principles of Rhetoric’), by saying that it will provide for the formation of the young pupils up until their studies of rhetoric and poetics (the letter of introduction to the 1493 edition edited by Orlandi, Dionisotti 1975: 165). The Haguenau edition from 1522 (HAB 114 Quod (1)) is based on the 1508 edition (Jensen 1998: 248), published between 1494 to 1515 and copied from the Tübingen edition from 1516. Alternatively, the compendium is called Grammatica latina Aldi Manutij and Rudimenta Aldi Jensen 1998: 274).

1.1. Locations of the First Edition![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

-

Aldi Manucii Bassianatis Institutiones grammaticae . Venice: Torresano, Andrea, 1493

2. Author![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

Born in Bassiano, near Rome, ca 1450, Aldus Manutius (the latinized name of Tebaldo Manucci) received his early education in Rome where he completed his studies in Latin language and literature at the University of Rome. The two teachers that he later mentions from his education in Rome are Gaspare da Verona, who was acquainted with Guarinus Veronensis (c. 1400-74), and a Veronese philologist Domizio Calderini (1446-78). Gaspare, the author of a grammatical treatise Regulae Grammaticales, was named Professor of Rhetoric at the university and was Aldus' teacher of Latin supposedly between 1460 and 1473 (Grendler 1984: 8). Calderini, while also holding a prestigious position at the papal palace, was hired by the university in 1470 to lecture on Latin authors, which he did with remarkable success (Lowry 1979: 48-49); he also edited Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria among other things. While studying under these humanist sholars, Aldus not only acquired an enduring love for the Classics but also became convinced that the study of the Greek language and literature was fundamental for the ‚studia humanitatis‛, and in the late 1470s he left Rome in order to study Greek and Latin with Guarinus' son Battista (1435-1505) at the University of Ferrara. His Greek studies at Ferrara obviously had a more fundamental impact on his professional life than his studies at the faculty of humanities at Rome. In Ferrara he also became familiar with Pico della Mirandola, a Renaissance philosopher, whose Oration on the Dignity of Man became something of a manifesto of the Renaissance.

Aldus regarded himself above all as a teacher and a pedagogue, and he had a chance to promote the ‚bonae artes‛ in a classroom at the highest level of society. According to a legal document from 1480, Aldus was a tutor to the young princes Alberto I (1475-1531) and Leonello Pio (1477-1571) of the north Italian town of Carpi from about 1483 to 1489 (Grendler 1984, 9). He composed his grammatical manual while he was tutoring the Pio brothers for six years or so. In this letter to Catarina Pio in 1487 he said that he had written it for the use of her sons; the 1493 version is also presented to Alberto Pio, his former pupil and future patron. We can infer his educational ideas from the introductory letters to his own grammatical works and the editions published by his press. In the edition of Aristotle's works, addressed to Prince Alberto, Aldus pointed to the importance of the knowledge of Greek literature in his own time: „all agree that it does not belong only to young pupils, who are studying it in great numbers, but even the old are now learning Greek“ (Dionisotti 1975: 6). In his edition of Lascaris' Erotemata in 1495, he wrote: „I have decided to dedicate all my life to the benefit of mankind. God is my witness that there is nothing that I desire more than to be useful for other people“ (Dionisotti 1975: 4). Aldus was convinced that men had to read Greek and Latin classics in order to become truly learned and virtuous and this mission also became part of his role as a publisher and printer.

At the age of forty, Aldus established his firm in partnership with Andrea Torresani and Pierfranceso Barbarico (d. 1409 in Venice, where he moved to about 1489 (Grendler 1984: 15). Aldus' role in the printing of Greek texts became pioneering, and by the time of his death in 1515, almost all the canonic Greek authors were accessible (Hexter 1998: 143). Among his first publications appearing in late 1494 and early 1495 were not only Greek pedagogical works, such as Constantine Lascaris' Erotemata and Theodore Gaza's Greek grammar, but even an edition of Apollonius Dyscolus' highly theoretical treatise on syntax. This is probably because Priscian, one of the favourite grammarians of the humanists, had praised Apollonius and his son Herodian as the best ancient grammarians. Aldus quotes these Priscianic passages in his introductory letter to his Apollonius edition, published in 1495 (edited by Orlandi, Dionisotti 1975: 8). As regards Latin grammatical works, Aldus published Varro's De lingua latina revised by Pomponius Laetus and Rhodandello in 1498 (Dionisotti 1975: 17). Aldus' first famous publication was the ‚editio princeps‛ of Aristotle's complete works (except for the Poetics and Rhetoric which were not yet available) in five large folio volumes between 1495 and 1498, and other editions of Greek texts followed suit, altogether about thirty first editions of Greek literary and philosophical texts (Grendler 1984: 16-18). As a grammar teacher and at the early stage of his printing career, Aldus used as his cognomen Bassianus, but in 1497 he began to prefer Romanus, clearly identifying himself with his humanistic education at Rome, and from 1513, he added to his name the cognomen Pio − the title he received while tutor to the two Pio brothers (Dionisotti 1975: xiii).

In a dedicatory letter to the 1493 edition of his grammar, Aldus mentions some other grammatical works produced by him: „Graecas institutiones et exercitamenta grammatices, atque utriusque linguae fragmenta, et alia quaedam valde (ut spero) placita“. In the letter to Catarina Pio in 1487 he mentions the following works, which are probably what he had referred to as ‚alia quaedam‛: a treatise on Greek and Latin accents, the Panegyrici Musarum, a Libellus graecus tamquam isagogicus, and a work on the writing of poetry. The Panegyrici Musarum (’A eulogy to the Muses’), praising the value of Classical education, was Aldus' first work published probably in 1489. If the Libellus graecus is the De literis (ac diphthongis) Graecis, as Julius Schück has argued (Schück 1876: 7), all these texts have been published, except the Exercitamenta grammatices atque utriusque linguae fragmenta. The manuscript had disappeared and his son Paulus thought it had been stolen (Bateman 1976: 227). Bateman, who has published all the references to the Fragmenta in Aldus' extant works, thought that the Fragmenta was probably finished by 1508 (Bateman 1976: 231). The Graecae Institutiones was written in the 1480s and published in 1515. De literis graecis ac diphthongis, a collection of short sections on the Geek alphabet, prayers and poems, first appeared as an appendix to the 1495 edition of Lascaris' Erotemata, entitled Alphabetum Graecum, and was later integrated into all the other editions of Lascaris' grammar as well as to the fourth edition of Aldus' own Latin grammar in 1514 (Bateman 1976: 230). The work on poetry is probably Aldus' metrical introduction to the lyric poems attached to the second edition of Horace's Poemata, published in 1509.

3. Contents![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

The author uses the catechetical method systematically throughout the treatise, and each section is concluded with parsing exercises cast into the form of ‚quaestiones‛. This method was heavily used in the medieval Ianua-text. Both made-up examples and classical ones are used; many Greek examples occur especially in the treatment of figures.

The introduction to syntax (‚oratio, constructio‛), receives a great deal of attention, taking into account even subclauses and sentences other than declarative. Resorting to Priscian's definition, speech is first divided into that which renders a perfect sense, that is a complete sentence, such as ‚veritas odium parit‛ and that which does not; examples of the latter are what we know as embeddings (e.g. ‚me amare deum‛) and subclauses (e.g. ‚cum venissem in Cumanum‛). The perfect expressions are further divided into five kinds of sentences: interrogative (‚quae tanta fuit Romam tibi causa videndi‛), imperative (‚accipe nunc danaum infidias‛), optative (‚Ut nunc utinam surdis auribus esse velim‛), vocative (‚promissi testis adesto diis iuranda palus‛) and enuntiative (‚navigat Aeneas‛). Using the parsing method, the author proceeds to ask a series of questions: „Amo deum quae pars est grammatices? Oratio. Quare? Quia est congrua dictionum ordinatio ad aliquid significandum. Quae oratio est? Perfecta. Quare? Quia perfectum habet sensum. Cuius speciei orationis perfectae? Enuntiativae. Quare? Quia amorem meum erga deum enunciat“. Aldus called these ‚species‛ of verbs as did his teacher Gaspare da Verona.

Turning to discussing the individual parts of speech, Aldus continues to use the catechetical method. The definition of the noun is drawn literally from Donatus, preserving even his original examples („Nomen est pars orationis corpus aut rem proprie, communiterve significans, proprie ut Roma, Tyberis, communiter, ut urbs, flumen“). It is followed by a division of nouns into substantives and adjectives, which are identified by formal criteria, by means of the number of articles that they can be associated with, as was customary in Italian grammars of Latin: „Quod est nomen substantivum? Quod habet unum articulum ut hic poeta vel duos ad summum ut hic et haec advena. Quod est nomen adiectivum? Quod habet tres articulos ut hic et haec et hoc foelix“. But Aldus does not avoid notional definitions either; adjectives are said to be added to substantives in order to specify their quality and quantity, e.g. ‚altum mare, coelum profundum, rotundum volubile, nix alba, niger corvus‛. The noun is further divided into proper as pertaining to one person and common pertaining to many. The accidents are those of Priscian: ‚species, genus, numerus, figura et casus‛. After a discusion on the derivation, gender, and declension of nouns, as based on the genitive endings and final letters, several nouns are examined by using the parsing method.

Starting from the headword ‚poeta‛, familiar from the popular elementary textbook Ianua, questions are raised concerning every possible aspect of the grammatical structure of words. The pupil is moreover expected to be able to define items of metalanguage, such as ’case’, explain philosophical terms, such ‚ad aliquid‛, and justify grammatical phenomena by answering ’why’ questions: (c iiii r) „Poeta quae pars orationis est? Nomen. Quare? Quia significat substantiam et qualitatem, propriam vel communem, cum casu, sed poeta communem, Vergilius vero propriam. Iulus cuius speciei? Primitivae. Quare? Quia a nullo derivatur. Iulius cuius speciei? Derivativae. Unde derivatur? Ab Iulo. Hic poeta cuius generis? Masculini. Quare? Quia praeponitur ei in declinatione unum articulare pronomen hic.“ After this examination, paradigms of nominal declensions follow, involving many Greek proper and common nouns, e.g. ‚Penelope, Anchises, Troiugena, Aeneas, Aeneades, Iphigenia, Tethys, Demphon, titan, Oedipus, Amathus, Amaryllis, Chremes, Dido, Paris, Iupiter, melos‛ and many others. When discussing the Greek genitive ‚huius Penelopes‛, Aldus makes a digression into one of his favourite topics, the pronunciation of Latin and Greek in Antiquity. The Greek genitive in -es was pronounced as long e rather than long i in Antiquity, as he points out.

The noun section is concluded with an account of composite nouns (c ii r), the declension of the numerals (c iii r), the grades of comparison and the heteroclite nouns (c iv r), that is, nouns that have irregular declension. The last section was less elaborate in the 1493 and 1501 editions, consisting of a large number of mnemonic verses, whereas in the 1508 edition they receive a methodical exposition covering circa fifteen pages, being concluded with mnemonic verses. (The verses no longer appear in Aldus' grammar after 1514, Jensen 1998: 257.) This section involves a large number of examples drawn from classical literature.

The pronoun section opens with Priscian's definitions in a slightly altered form: ‚Pars orationis declinabilis, que pro uniuscuiusque nomine accipitur personasque finitas recipit‛. Priscian had restricted the use of pronouns to substituting proper nouns (‚pro nomine proprio uniuscuiusque‛) − the feature that Aldus has excluded from his own definition − but he nevertheless agrees with Priscian's position. The Priscianic accidents ‚species, genus, numerus, figura, persona‛ and ‚casus‛ are listed. This section is dominated by parsing exercises; the ‚interrogationes‛ cover roughly seven pages.

The section on the verb opens with Priscian's definition adopted with a minor modification: „Pars orationis declinabilis vel agendi vel patiendi vel utriusque significativa cum modis et temporibus sine casu“. It is followed by Priscian's accidents: ‚genus, tempus, modus, species, figura, persona, numerus‛ and ‚coniugatio‛).

The remaining parts of speech are discussed in a concise manner, making use of traditional definitions and accidents and providing a large amount of parsing exercises. It is noteworthy that in the two final sections, the ones on conjunctions and interjections, Aldus uses mnemonic verses in order to facilitate the remembering of long lists. The various types of conjunctions are cast into the form of three verses: „Co. conque, et subcon. dis. subdis. adiuque. Causal (= copulativa, continuativa, subcontinuativa, disiunctiva, subdisiunctiva, adiunctiva, causalia). Approbat, adversa, distri, discreque. du, dique (= approbativa, adversativa, distributiva, discretiva, dubitativa, diminutiva). Abnegat, effecti. collecti. his adiice complet (= abnegativa, effectiva, collectiva, completiva)“. The various significations of interjections are shortened into the following verse: ‚Gaudentis.risus.mirantis.dolque pavorumque (=gaudentis, ridentis, mirantis, dolentis, expavescentis)‛.

The book devoted to syntactical theory is highly methodical (49), proceeding by means of definitions and divisions and using the catechetical method. The general principles are outlined first. The construction is first defined (‚Debita dispositio partium orationis in ipsa oratione‛), then divided into three; those which are congruent in meaning and in form, e.g. ‚Phyllis amat Corylos‛; those which are congruent in meaning but not in form, e.g. ‚Turba ruunt, populus currunt, gens armati‛; and those, which are congruent in form but not in meaning, e.g. ‚Venetiae in sinu Adriatico sitae, abundant divitiis‛.

Concord and government, the cornerstones of medieval syntactical theory, are now regarded as the accidents of construction. Concord expresses itself in three constructions: the nominative agrees with the verb in number and person, e.g. ‚ego amo, tu amas, ille amat‛; the adjective agrees with its headword in number, case and gender, e.g. ‚Ulysses astutus, Penelope pudica, arma crudelia‛; and the relative agrees with its antecedent in number and gender, e.g. ‚Aeneas qui, Dido quae, Ilium quod‛. These three concords of medieval origin occur standardly in humanistic grammars (e.g. Perottus, Sulpitius, Lily and Colet, see Luhtala 2014: 62 and Luhtala, 2018.). Each of these relations of concord are further divided into subtypes. The nominative agrees with the verb in number and person. Parsing exercises follow immediately after: „Ego amo, quae concordantia est? Nominativus cum verbo. Ostende nominativum ego, ostende verbum amo. Concordatne? Concordat. Ostende ego est numeri singulari et amo singularis. Ego est personae primae et amo primae, ergo congrue dicitur ego amo, quia concordat nominativus cum verbo in numero et in persona. Quare ego est numeri singularis? Quia singulariter profertur. Quomodo? Singulariter ego amo. Quare ego est personae primae? Quia omnia nomina et pronomina sunt tertiae personae, exceptis ego, quod est personae primae, et tu secundae“. This minute analysis is applied to each type of concord, specifying whether it is congruent in signification or form, or in both. The presence of a large amount of such exercises throughout Aldus’ manual shows that he favours a highly analytical approach to language teaching.

One of the peculiarities of Aldus' approach is that he also quotes incorrect examples asking the pupil to explain why they are not well-formed: „Dicereturne congrue ego amamus? Non. Quare? Quia ego est numeri singularis et amamus pluralis et sic discordaret nominativus a verbo in numero“. He goes so far as to encourage the pupil to form incorrect sentences in his discussion on the concord between the relative pronoun and its antecedent: „Dic incongrue in genere duntaxat. Aeneas quam. Quare dicitur incongrue? Quia Aeneas est generis masculini, et quam foeminini. Quare non discordat etiam in numero et in genere? Quia Aeneas est numeri singularis et quam similiter. Fac discordat in numero et genere, Aeneas quarum. Quare sic? Quia Aeneas est numeri singularis et quarum pluralis. Aeneas est generis masculini et quarum foeminini. Ergo Aeneas quarum discordat in numero et in genere.“

Turning to the construction of each part of speech, Aldus first raises the general question of which parts of speech are capable of governing (another part) after them, which is a typically medieval theme. Both personal and impersonal verbs, the noun, participle, preposition, adverb and interjection are given in answer. Then he proceeds to deal with verbal syntax, based on the five types of ‚genus verbi‛, as had been customary in medieval Latin grammars in Italy for a couple of centuries. First, however, the verbs are divided into personal and impersonal, which is another typically medieval division. The active verbs are divided into ten subtypes, most of which are the same as can be found in other humanist grammars, Guarinus' and Sulpitius' Regulae. Lists of examples of each type are given, with vernacular translations, and mnemonic verses are used throughout. The medieval idea of a logical word order, the nominative preceding and the other arguments following the verb.

- 1. The first type of active verbs has a nominative agent and a patient in the accusative, e.g. ‚ego amo Deum, tu vendis libros, ille scribit litteras‛. Examples: ‚verbero as avi atum battere, video es di sum vedere, facio cis feci ctum fare‛.

- 2. (53) The second subtype of active verbs is construed with the genitive in addition to the nominative and accusative, such as ‚Graeci impleverunt equum armatorum militum‛. He further explains that prices can be expressed with the ablative case. Examples: ‚vendo dis didi ditum vendere, emo is emi emptum comprare‛.

- 3. (i vi v) The third subtype of active verbs is construed with the dative in addition to the accusative ‚a parte post‛, e.g. ‚homo pius dat elemosynas pauperibus‛. Examples: ‚scribo is psi ptum scrivere, lego is legi ctum leger‛.

- 4. (i vii v) The fourth subtype of active verbs is construed with two accusatives, such as ‚ego doceo te grammaticam‛. Examples: ‚flagito tas tavi tatum‛.

- 5. The fifth subtype of active verbs is construed with the ablative in addition to the accusative, for instance, ‚video te oculis‛. He tells not to use the preposition here: ‚Cave dicas cum hasta, nam cum instrumentum significamus tacemus praepositionem‛. Examples: ‚inficio cis feci ctum tingere, munio nis nivi nitum fortificare‛.

- 6. The sixth subtype of active verbs is construed with the ablative and a preposition in addition to the accusative, such as ‚ego audivi et didici multa a praeceptoribus meis, a Gaspare Veronensi grammatico egregio, a Baptista Guarini filio viro utriusque linquae quam doctissimo‛. Aldus mentions here two of his most important teachers. Examples: ‚audio dis civi ditum odire, edisco scis didici imparare‛.

- 7. The seventh subtype of active verbs is construed with the dative in addition to the nominative, e.g. ‚boni pueri libenter audiunt magistris‛. This type is not present in the other Humanist grammars. Examples: ‚ausculto tas tavi tatum obedire, recipio pis cepi ceptum promittere.‛

- 8. The eighth subtype of active verbs is construed with the infinitive/oblique in addition to the nominative, ‚ego credo esse doctus et ego credo me esse doctum‛. This is an instance of indirect speech, which is not normally included in these lists. Examples: ‚spero ras ravi ratum sperare, cupio pis vi pitum desiderare‛.

- 9. The ninth subtype of active verbs is construed with the nominative before and after the verb, e.g. ‚doceo sedens, oro astans, adoro supplex‛.

- 10. The tenth subtype of active verbs is construed with the nominative before the verb absolutely, e.g. ‚amo, lego‛.

There are also ten subdivisions of passive verbs; their subtypes are less carefully analyzed. The seven types of neuter verbs and deponent verbs joined together largely follow a similar classification as the active, a large number of examples being listed in each case.

then follows a discussion of expressions of place, by means of both adverbs and noun phrases; then Aldus returns to the syntax of verbs, discussing verbs of ‚genus commune‛, impersonal verbs, infinitives, gerunds, and supines. In the discussion on infinitives, the medieval term for subject (‚suppositum‛) incidentally surfaces: ‚Reguntne infinita ante se suppositum verborum suorum‛? Aldus pays more attention to the use of the infinitive in emebedded constructions, understanding them as replacing subclauses, than most other grammarians. Finite clauses initiated with the conjunctions ‚quod‛ or ‚quia‛ can, according to Aldus, be transformed into an infinitive, as in the following examples: ‚credo quod tu es aut eras indoctus - credo te esse indoctum, scio quod tu ivisti aut iveras Romam - scio te ivisse Romam‛. He points out, however, that the use of the finite verb and conjunction is less elegant Latin than the embedded construction. This section concludes with sections on comparison, relative pronouns, interrogative, distributive and partitive nouns; the construction of the different cases, participles and patronymics. The participle section also involves a point of controversy, in which Aldus disagrees with Valla. Finis. The Book IV is devoted to metrical issues, discussing metrical feet, syllables, accents, punctuation.

The final topic is drawn from the pronoun section, explaining the difference between ‚quis‛ and ‚uter‛, which is such that ‚quis‛ is said of two or more but ‚uter‛ is only said of two; ‚quis‛ differs from ‚qui‛, in that ‚qui‛ is used relatively, interrogatively and infinitely; wheras ‚quis‛ is used infinitely and interrogatively. In the remaining last three topics the Italian vernacular is used: „Quot requiruntur in nubo, nubis? Tria: in prima parte quelli chi marida in ablativo a vel ab mediante, el sposo in dativo, la sposa in nominativo, ut a me nupsit Petro aliqua“.

4. Context and Classification![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

Aldus' Institutiones grammaticae is a fairly elementary Latin grammar as is suggested by the word ‚rudimenta‛ in the title of the 1501 edition. Furthermore, in his letter to Catarina Pio in 1487 Aldus tells us that he had compiled his grammar in order to teach young children quickly and effectively. In the introductory letter to the first edition of the Institutiones, he repeats the same idea and expresses his dissatisfaction with the existing works of which one is too short and concise (‚brevis et concisus‛), another too diffuse and ostentatious (‚admodum diffusus et vanus‛), and a third utterly inept and indigestive (‚perineptus et durus‛). Moreover, „in my opinion no one has yet written a grammar suitable for teaching children“ (ed. Orlandi in Dionisotti 1975: 41). Aldus is making an important point here; in Antiquity and the Middle Ages no clear distinction was drawn between the ways in which to teach a child as opposed to an adult and it seems to have been one of the aims of Aldus Institutiones grammaticae to be something of a pioneer in this respect.

The contents of the manual also bear a number of features pointing to its elementary nature. Using the catechetical method throughout, it follows the order of the parts of speech of Donatus and his definition of the noun; most of Aldus' definitions, however, depend on Priscian's Institutiones grammaticae. , which he used directly. Moreover, the introductory section contains religious reading material, which was regularly used for teaching literacy. Such material was not normally printed together with grammatical works, but for instance Perottus' Rudimenta contains similar material, as does also the standard edition of the King’s grammar (or the Shorte Introduction of Grammar ascribed to William Lily>

and John Colet), which became the authorized textbook of Latin grammar in England for several centuries. The inclusion of such material in a grammatical manual reflects Aldus' well known piety and his professed aim of imparting to his pupils not only good literary style, ‚bonas literas‛, but even more importantly, high moral standards, ‚sanctos mores‛. If both could not be achieved, as he points out in the preface to his grammar (a ii rv), he recommended that the teachers strive for the moral standards. The examples are largely made-up and pertain either to the ancient or contemporary world. Mnemonic verses are used in some sections. This feature in Aldus is regarded as conservative by Jensen (Jensen 1998: 256-257, 262), but there is hardly any reason for this. The popularity of mnemonic verses continued well into the Renaissance and the humanists had no problems with this approach; Valla composed a grammar in verse in order to substitute the popular Doctrinale. Despauterius' Commentarii, the most popular early modern grammar in the Low Countries and France, made use of mnemonic verses, and verses were added to some editions of Sulpitius' grammar.

Aldus' grammatical manual was the outcome of the experience that he had gained by tutoring the Pio brothers for over six years. In the introductory letter to the 1493 edition, Aldus describes the circumstances in which his manual emerged and his motivation for engaging himself in this arduous work. He was neither seeking glory − for what glory is there in such a humble enterprise? − nor was he working in the hope of profiting from it; nor did his grammatical works come out spontaneously. They were written at the behest of friends (in the 1501 edition, ed. Orlandi in Dionisotti 1975: 41 and because he had been forced to instruct his pupils using a concise and pleasant method. He had been unable to teach as effectively as he wanted, because he was dissatisfied with the existing textbooks, even with the learned ones that had been composed accurately. In the letter of introduction to the 1501 edition addressed to the teachers, Aldus warns that the teachers should not ask their pupils to learn by heart the grammatical rules, unless a very short compendium is at issue; instead they should study grammatical manuals carefully and have an excellent knowledge of nominal declensions and verbal conjugations. If they learn by heart Aldus' manual or one of the verse grammars, they will unlearn what they learned in a couple of days. This is what had happened to him when he was a boy and a young man: he had learnt the gender rules and the preterites of verbs carefully and forgotten them in no time. Moreover, put off by the difficult subject matter and the tedious style, the pupils will turn away from school and begin to hate the studies that they are unable to learn. What the pupils should rather learn by heart are the works of Cicero and Vergil, who could provide models for good style. Earlier on, however, he had recommended that the Pio brothers should learn by heart his treatise on Latin and Greek accents that he had written for them in a letter to Catarina Pio in 1487 (ed. Orlandi in Dionisotti 1975:I, 160); from this we can infer that the pronunciation of the ancient languages was important for his pedagogy.

Aldus never condemned the medieval approach to grammar, nor did he avoid using philosophical terms employed by Priscian, such as ‚

substantia‛ and ‚qualitas‛ in describing the noun, inspite of the elementary nature of his manual. He also integrated all the subtypes of common nouns present in Priscian's Institutiones grammaticae into his framework; many of them (e.g. ‚ ad aliquid, quasi ad aliquid, nomina generalia‛ and ‚ specialia‛) are of philosophical origin. (They were absent from the first edition.) As a matter of fact, Aldus favours a highly analytical approach to language. His predilection for the analytical method is attested by the numerous parsing exercises, which invite the pupils not only to identify but also analyze and explain grammatical phenomena. Thus, Aldus does not align himself with the grammarians, such as Guarinus, who wanted to simplify the analytical apparatus of grammar. (Guarinus' Regule is actually a good candidate for being the concise work Aldus mentioned disapprovingly.) On the contrary, in his introductory letter to his edition of Aristotle's philosophical works, he recommends Aristotle's Organon. as the necessary instrument for the study of all sciences, which is precisely what the medieval approach to language science represents: „Est enim instrumentum ad omnes scientias pernecessarium: hoc enim genus et speciem cuiusque rei cernimus, hoc definiendo explicamus, hoc tribuere in partes, hoc quae vera, quae falsa sunt iudicare possumus, cernere item consequentia, repugnantia videre, ambigua distinguere“. Aldus had an interest in philosophy, and in his only surviving letter to Aldus in 1490, Pico encouraged him to continue to pursue his philosophical interests (‚accinge ad philosophiam‛) (Opera omnia: V v r).

While being fairly traditional in its close adherence to the doctrine of Donatus and Priscian, the two favourite grammarians of the humanists, Aldus' manual nevertheless proved innovative in some pedagogical respects. Aldus' preliminary topics included a list of all possible Latin syllables with two or three letters, which is unique to his manual in this period but may reflect an older and more widespread approach to the teaching of literacy (Lucchi 1978: 593 - 630). Aldus anticipates that his readers might ridicule them as being very elementary or unsophisticated (‚perquam rudia‛), but does not hesitate to defend his approach, which he finds helpful in teaching pronuntiation and orthography; in compiling these lists, as he tells us, he has followed ancient grammarians (a ii rv). Of great significance is also the short introduction to the Hebrew language included in the preliminary material of the manual of the Haguenau edition. This introduction proved popular in Germany, receiving eight separate editions; its success was associated with the interest in the Kabalah arising in the circle of Reuchlin (Jensen 1998: 269-270). In the Haguenau edition Aldus' note to the reader points out that a knowledge of Hebrew is fundamental for the understanding of the Sacred Sriptures as well as for the understanding of the art of Pythagoras and the Kabalah. The importance of the knowledge of the Greek language to the study of Latin was fundamental for Aldus' pedagogy, and he takes an opportunity to defend it in his account of the patronymics, which he has expanded with material relevant for the knowledge of the Greek language and literature. Anticipating that his pupil, while studying Latin, might wonder why he should learn so much about the Greek patronymics, he points out that the pupils should ideally be given formation both in Latin and Greek simultaneously. They should start by learning the Latin of their own day and not long after they should occupy themselves with Roman and Greek literature. Among the novel linguistic aspects was Aldus' awareness of the differences between contemporary and ancient pronuciation of Greek and Latin, which he began to observe in the 1508 edition of his grammar. This interest he shared with Erasmus, who collaborated with Aldus during his stay in Venice in 1508.

Like many other humanists, Aldus recommended the use of ancient grammatical sources, such as Priscian, Diomedes, Varro, Servius, Sergius, Phocas, Aulus Gellius, and Asinius Capito, as well as Valla and Perottus among his contemporaries. He also found inspiration in Quintilian's Institutio oratoria. , rediscovered by Poggio Bracciolini in 1416. Aldus was influenced not only by some of Quintilian's methodical principles, but also by the importance that he had ascribed to the grammarian’s profession. In his footsteps, Aldus praises grammar (including the study of literature)„as a necessity for boys and the delight of old age, the sweet companion of our privacy and the sole branch of study which has more solid substance than display“ (I,4,5). Like Quintilianus, Aldus was aware of the low esteem in which this profession was held by his contemporaries inspite of its fundamental importance for all subsequent education and the moral formation of the pupils. Aldus reminded that the teachers should not regard themselves only as guides and teachers of young people but even as their parents. They were responsible for forming the character of young boys, who may be future lawyers, princes, rulers. bishops, philosophers or even popes. In the introductory letter to the 1493 edition, he laments that he was not able to apply his genius to a more worthy subject, especially as he saw how many dull-minded (‚obtuso ingenio‛) people, who had chosen to delve into a worthy subject, had become prominent and were being universally praised, whereas he and the likes of him not only remained without praise but were even the object of ridicule. He also anticipated that not everybody was going to approve of his manual, similarly as he had not been satisfied with the works of others. What he had achieved, however, is that he is content with what he has achieved: to teach young pupils using a simple and efficient method. If he had managed to satisfy even others, let the praise go to Jesus Christ, who had given to him that by which he was able to satisfy and profit other people (ed. Orlandi in Dionisotti 1975: 166). This lamentation is absent from the later editions probably because Aldus' labors were gradually being rewarded and he had acquired a solid respectability. In a letter written in 1507 to Aldus, Erasmus praised Aldus' publishing work comparing it with the labors of Hercule and predicting him an eternal fame and glory.

5. Reception and Influence![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

Altogether sixty editions of Aldus' manual have been traced, twenty-eight of them coming from Italy; of these, twenty-four from Venice, two from Toscolano and two from Florence. There are fifteen German editions and seventeen from France from between 1510 and 1531, sixteen from Paris, and one from Lyon (Jensen 1998: 247-250). The amount of printed editions that Aldus' grammatical manual received shows that it was less popular than the humanist grammars of Perottus, Melanchthon and the authorized grammar traditionally associated with William Lily and John Colet. Neverthess it managed to be influential for over a hundred years, and − what is remarkable − it continued to be used for such a long period without undergoing significant changes (Jensen 1998: 252).

In addition to the three editions in quarto, in 1501, 1508 and 1514, the Aldine press published after nine years yet another edition (1523) in quarto. Paulus Manutius published six editions in octavo over a period of ten years from 1558, and in 1575, the younger Aldus, published one or two editions of the work. (For more details, see Jensen 1998.) Editions published outside Italy form two distinct groups, of which the earlier includes four German editions from Leipzig in 1510, 1511, 1514, and 1516; one from Tübingen (1516), one from Haguenau (1522) and three from Cologne (1517, ca. 1520, 1522). The Leipzig editions are based on the Aldine 1501 edition and the others on the 1508 edition (Jensen 1998: 248). Some editions of Aldus' grammar underwent significant changes in the course of the sixteenth century. The last edition of his grammar was published in 1586 by Petrus Dusinellus.

Aldus' name is among the four most renowned Italian grammarians that the Flemish scholar Jean Despauterius mentions in a preface to the first part of his grammar in 1512 (vol. 2, 379); the others are Sulpitius, Perottus, and Antonius Mancinellus ( Commentarii gramm. Paris, 1537, b 4 v). Despauterius knew Aldus', grammar but fails to refer to it in his grammatical work; Sanctius also mentioned Aldus' name. He was also mentioned in Erasmus' De ratione studii ASD (1-2, 148) as one of the best grammarians alongside Perottus. Vives (1492-1540), one of Erasmus' students, recommends the use of Donatus as an elementary textbook and praises the works of Sulpitius, Perottus, Nebrissensis, Aldus and Melanchthon ( De Disciplinis libri XII). In Germany, his name appeared in the list of authors recommended by Heinrich Bebel in 1512, together with Sulpitius, Perottus, Jacobus Henrichmannuss; the German work of Henrichmannus (1482-1561) also occured in this list; he was among the first users of Aldus' manual in his own grammatical works (Jensen 1998: 266-267). By 1520 Aldus' grammar ceased to be printed in Germany, where grammars compiled by native scholars such as Iohannes Turmair Aventinus and Jacobus Henrichmannuss began to be preferred to Italian grammars.

There was a later revival of interest in Aldus' grammar in Germany, whereby its success can to some extent be related to the effects of the Counter-Reformation. All these later editions come from Cologne, which was the publishing centre of the Counter-Reformation. When the religious world became polarised, a suitable alternative had to be found for Melanchthon's grammar, which had become the standard textbook in Protestant countries, the Roman Catholic Aldus with his reputation for piety emerged as an ideal candidate and his name became authoritative. When Petrus Homphaeus compiled a Latin grammar in 1542, he associated it with Aldus' name, although it bore very little resemblance to Aldus' work. The four books of Aldus' compendium was reduced to two and his definitions and examples had undergone significant alterations. Moreover, his book on syntax was replaced by a short syntactical treatise, originally compiled by William Lily and revised by Erasmus, entitled Absolutissimus de octo partium orationis; another syntactical section based on Despauterius was appended to it; and Aldus' account of the figures of speech was replaced by the one found in the grammar of Petrus Mosellanus (Jensen 1998: 268-26). Thus, Aldus' grammar became yet another textbook in the history of linguistics, along with Melanchthon's Grammatica latina and Donatus' Ars minor, which circulated bearing the authoritative name of its original compiler while being constantly reworked for new purposes.

6. Bibliography![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

-

Bateman, John. 1976. Aldus Manutius' Fragmenta Grammatica. Illinois Classical Studies I, 265-261.

-

Colombat, Bernhard. 1999. La grammaire latine en France à l’âge Classique: théories et pédagogie.. Ellug: Universitè Stendahl.

-

Dionisotti, Carlo. 1975. Aldo Manuzio Editore. Dediche, prefazioni, note ai testi. Introduzione di Carlo Dionisotti. Testo latino con traduzione e note a cura di Giovannni Orlandi. Milano: Edizioni il Polifilo.

-

Erasmus Roterodamus. De ratione studii.. ASD = Opera omnia Desiderii Erasmi Roterodami, vol. 1-2. Ed. Jean-Claude Margolin. Amsterdam, 1971.

-

Grendler, Paul. 1984. Aldus Manutius. Humanist, Teacher, and Printer. Providence, Rhode Island: The John Carter Brown Library.

-

Hexter, Ralph. 1998. Aldus, Greek, and the Shape of the 'Classical corpus'. Aldus Manutius and Renaissance Culture. Ed. Zeidberg, 143-160.

-

Jensen, Kristian. 1998. The Latin Grammar of Aldus Manutius and its Fortuna. Aldus Manutius and Renaissance. Ed. Zeidberg 1998, 247-285.

-

Lowry, Martin. 1979. The World of Aldus Manutius. Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice.. Oxford: Blackwell.

-

Lucchi, P. 1978. La Santacroce, il salterio e il babuino. Libri per imparare a leggere nel primo secolo della stampa. Quaderni Storici, 38, 593-630.

-

Luhtala, Anneli. 2014. Scholastic Influence on Syntactical Theory in Pedagogical Grammars. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenscaft, 51-70.

-

Luhtala, Anneli. 2018. A Case Study in Language Pedagory of Three Humanist Treatises on Syntax from Early Modern England. The History of Language Learning and Teaching I. 16th - 18th Century Europe. Ed. Nicola McLelland and Richard Smith, 51-70. Maney Publishing.

-

Pastorello, E. 1957. L'epistolario manuziano. Biblioteca di bibliografia italiana, 30. Florence.

-

Pico of Mirandula. 1531. Opera omnia Pici Mirandulae.

-

Schück, Julius. 1867. Aldus Manutius und seine Zeitgenossen in Italien und Deutschland. Berlin.

-

Scarafoni, Camillo Scaccio. 1947. La piu antica edizione della grammatica latina di Aldo Manuzio finora sconosciuta ai bibliografi. Miscellanea bibliografica in memoria di Don Tommaso Accurti. Ed. Lamberto Donati, 193-203.

-

Zeidberg, David S. (ed.). 1998. Aldus Manutius and Renaissance Culture.. Essays in Memory of Franklin D. Murphy. Acts of an International Conference Venice and Florence, 14 - 17 June 1994. Ed. David S. Zeidberg, with the assistance of Fiorella Gioffredi Superbi. Florence: Leo S. Olschi.

![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)