1. Title and Authorship![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

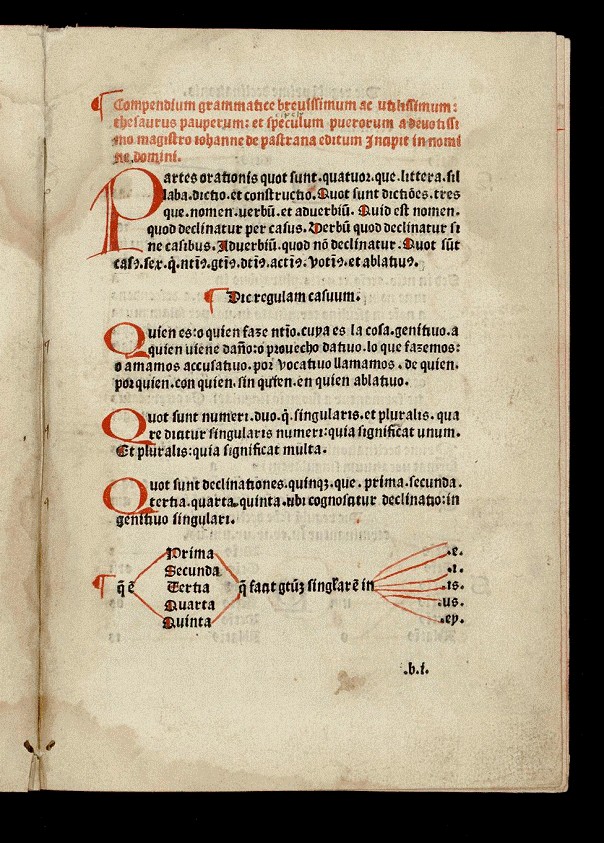

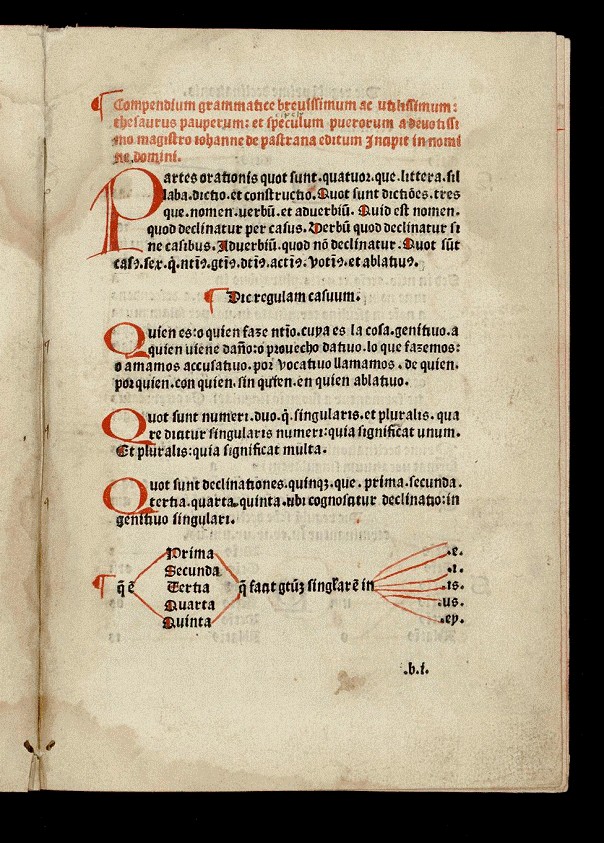

The grammar of Juan de Pastrana (fl. 1450) circulated in manuscript form amongst Spanish students during the 15th century. It is also known by its incipit Thesaurus pauperum siue speculum puerorum, and is the first published grammar book in Portugal (Lisbon, 1497). It was printed by the German printer Valentin Ferdinand of Moravia (fl.1450–1519) 1 and was edited by the Portuguese scholar Pedro Rombo (d.1533), professor of ‚new grammar‛ at the University of Lisbon.

The complete Portuguese edition is composed of three grammar books, Grãmatica Pastrane being the first one. It has 44 folia in 2° (or folio) (31 cm). The other both grammatical treatises have the same size and were written by Pedro Rombo (the second one) (15 folia), and by his predecessor as Latin professor at the University of Lisbon, António Martins (fl.1442) (the third one) (30 folia). They were printed in different dates. The Grãmatica Pastrane has not an explicit date, but it is plausible that it was published at the same time of the second book, i.e., Pedro Rombo’s grammar, viz., 27 May 1497 (‚milesimo quadringentesimo nonagesimo septimo, vi kalendas Junii‛ (Rombo 1497: bb10r.)). António Martins’ grammar is dated almost one month later, i.e., 20 June 1497 (‚Anno (…) milesimo quadringentesimo nonagesimo septimo. Die vero, xx mensis junii‛ (Martins 1497: d6r.)). We do not possess information concerning Pastrana’s manuscripts in Portugal, but we know that António Martins taught his grammar at the University of Lisbon in the middle of the 15th century.

1.1. Editions![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

-

Compe[n]diumgra[m]matic[a]ebreuissimu[m] ac utilissimu[m]: thesaurus paup[er]u[m][siue]spe[cu]lu[m]pueror[um]: a devotíssimo m[agist]roioha[n]ne de pastrana editum incipit in nomine domini. Salmanticae: typographia Nebrissensis, ca. 1485

- Biblioteca Universitaria de Santiago de Compostela Spain: Signatur: Res 19893(1)

-

Compe[n]diumgra[m]matic[a]ebreuissimu[m] ac utilissimu[m]: thesaurus paup[er]u[m][siue]spe[cu]lu[m]pueror[um]: a devotíssimo m[agist]roioha[n]ne de pastrana editum incipit in nomine domini. Toulouse: Henricus Mayer, ca. 1492

- Biblioteca Nacional de España Madrid: Signatur: INC/77(1)

-

Grãmatica Pastrane. Incipit compendium breue et utile: siue tractatus intitulatus: Thesaurus pauperum siue speculum puerorum editum a magistro Johãne de pastrana. Lisboa: Valentim Fernandes de Moravia, 1497

- Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal Lisbon: Signatur: INC 1425

-

[Joannis Pastrana rudimenta grammatic[a]ecu[m]commentariis.} Thesaurus pauperum finit cum suis comentariis in quo rudimenta grammatic[a]eartifícios[a]e atque ingenios[a]e per lustra[n]tur. Valenciae: Francisco Dias Romano, 1533

- Biblioteca Nacional de Catalunya Barcelona: Signatur: 8-I-1

-

Ioannis Pastrane opus gra[m]matic[a]e correctum et in pristina[m] formam redactum: quatenus ad declinationes, et genera nominu[m] pertinente, ac verborum coniugationes. Maioricis: Fernando Cansoles, 1545

- Biblioteca Nacional de España Madrid: Signatur: Mss/8616

3. Contents![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

The general approach of the Grãmatica Pastrane is clearly medieval. It is divided in the medieval division of the four parts of grammar (‚ethimologia, diasintastica, ortographia‛ and ‚prosodia‛) and uses a comprehensive selection of medieval tools of syntactical analysis, such as the question-answer technique, like in Donatus’ grammar, defining the majority of the grammatical concepts and presenting the main rules of the Latin grammar. It is also influenced by the Catalan-Aragonese ‚grammaticae proverbiandi‛. 2

The first folio is the cover, with the title ( Grãmatica Pastrane) on an ornamented page, with coat of arms of Portugal, an armillary sphere and an image of a teacher with his students (a1r.) and a dedicatory Letter of Pedro Rombo to his editor, Valentin Ferdinand (a1v.).

It starts with the section on ‚ethimologia‛, which is the longer part (25 folia), with the explanation of the three parts of speech — or, in his classification, the ‚dictiones‛, viz., ‚nomen, verbum‛ and ‚adverbium‛, contrariwise to Donatus’ eight ‚partes orationis‛ —, the cases and the paradigms of the five declensions. For Pastrana, the noun is a word ‚(dictio) quod declinatur per casus‛ ‘is declined by cases’ (a2r.), the verb is defined as a word that has not cases, ‚quod declinatur sine casibus‛ (a2r.), and the adverb is a word that it is not declined, ‚quod non declinatur‛ (a2r.). This section is divided into 21 chapters: the ‚partes orationis‛ (a2r.); the case rule (a2r.); the first declension (a2v.); the second declension (a2v.); the third declination (a3r.); the fourth declension (a3v.); the fifth declension (a3v.); the Greek nouns (a4v.); ‚proverbiandi‛ notes (a5r.); a summary of the syntactical rules (a5r.-v.); the conjugation of the verb ‚sum‛ (a5v.); an image (a tree) with syntactical rules (a6r.); two tables with verbal endings (a6v.-a7r.); another tree summarizing the division of constructions into transitive and intransitive (a7v.); the gender (a8r.); the prepositions (b2r.) 3 ; the irregular nouns (b2r.); degrees of comparison (b3r.); the verbal nouns (b3v.); the formation of nouns (b6r.); the irregular verbs (b8v.); and the conjugation of verbs (c2v.) (see Assunção et al. 2015). The ‚ethimologia‛ ends with the introduction, ‚sequitur de introductorio‛ (c8v.-d2v.) in which Pastrana explains some of the most common grammatical definitions following the Donatus’ model of question-answer, such as the grammar, the orthography, etymology, prosody, the three parts of speech or ‚dictiones‛).

Here Pastrana presents a more complete definition of the ‚dictiones‛, i.e.: the noun is defined as the ‚dictio declinabilis per quam uniuscuiusque rei esse uel essentia casualiter significatur‛ ‘a declinable word by which the being or essence of each thing is signified by means of the case’ (d1r.), and it has five accidents, viz., ‚casus, genus, numerus, persona‛ and ‚declination‛ (d1r.); the verb is a ‚dictio declinabilis cum tempore et modo actum essendi, agendi uel passiendi signifans absque casu‛ ‘an inflectional word with time and mode, signifying the act of being, acting or suffering, without case’ (d1v.), which has six accidents: ‚persona, numerus, tempus, modus, genus‛ and ‚conjugatio‛ (d1v.); and the adverb is a ‚dictio indeclinabilis ui nominis uel verbi significatiua consistens‛ ‘a word without flexion which is based on the power of the meaning of the noun or verb’ (d2r.).

Interestingly, the Portuguese edition has only once a text in Romance language / Portuguese, to present the nominal cases, in semantic and functional terms, following an approach very similar to a 14th century grammatical treatise of Portuguese origin (see Fernandes 2017: 242).

The second part, the ‚diasintastica‛ or ‚diasintetica‛, has only 5 folia and two chapters: ‚de regimine‛ ‘on government’ (d2v.); and ‚de constructione‛ ‘on construction’ (d5v.), which is divided into transitive and intransitive construction (regarding Pastrana’s main syntactical concepts, see Fernandes 2017).

The last two parts of grammar, the ‚ortographia‛ (aa1r.-aa7r.), with 7 folia, and the ‚prosodia‛ (aa7v.-bb6v.), with 8 folia, are not described in the question-answer methodology. Interestingly, the presentation of the majority of the orthographical rules start with the medieval expression ‚nota quod‛ ‘notice that’ and, at first time, Pastrana speaks of ‚omnes partes orationis‛ ‘all parts of speech’ (aa4r.) mentioning the conjunctions, prepositions, noun, pronoun, verb, adverb, participle and interjection (aa4r.).

The ‚ethimologia‛ is based mainly on Donatus’ ars minor, in spite of the division of the ‚partes orationes (dictiones)‛ being only three (‚nomen, verbum‛ and ‚adverbium‛), and on the Spanish ‚grammaticae proverbiandi‛, but Priscian’s grammar is the main source in the other parts (concerning Pastrana’s sources, see, e.g. Codoñer Merino 1996: 18-21; 2000: 22-26).

4. Context and Classification![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

The Grãmatica Pastrane is an elementary textbook of Latin grammar used as a manual in the University of Lisbon at the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century (see, e.g., Bonmatí 1989; Verdelho 1995; Lozano Guillén 1995, 1998; Codoñer 1996, 2000; Kemmler 2013; Ponce de León 2014, 2015). It reveals pedagogical concerns to be used during the first stages of the language education and uses visual methods in the language learning and teaching (see Fernandes 2019).

Pastrana’s grammar circulated as manuscripts in Spain, since 1462 as far as we know, and there were a few earlier Spanish editions, since approximately 1485, edited by Ferdinandus Nepos (fl. 1460-1492) (see Codoñer 2000: 39-43), and some further editions during the first half of the 16th century. A (partial) critical edition was published in 2000 by Carmen Codoñer Merino (b. 1936).

The Portuguese edition of Pastrana’s grammar has abundant bordering ‚scholia‛ by Pedro Rombo, schemes with the declensions and verbal suffixes, and images to summarize syntactical concepts and to help the students in the process of language (learning-) teaching, like the 1492 edition. Curiously, Pastrana never uses the verb ‘to learn’ (‚discere‛), but always ‘to teach’ (‚docere‛), including in the definition of grammar: „Ars docens congrue loqui, recte scribere et debite partes pronuntiare.“ ‘(grammar] is the art which teaches speaking properly, writing correctly and properly pronounce the other parts’ (Pastrana 1497: [c viii r.])

5. Reception![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

Pastrana’s grammar was very criticized, in Spain, by Elio Antonio de Nebrija (1441–1522) and, in Portugal, by Estêvão Cavaleiro (c.1460–c.1518), but their criticism was more for professional rivalry than linguistic or grammatical questions (see e.g., Gil 2002; Sánchez Salor 2002). In Portugal, there were personal conflicts between Estêvão Cavaleiro and Pedro Rombo, which motivated, for instance, the failure of all Cavaleiro’s applications to be professor of the University of Lisbon, where Pedro Rombo taught (see, e.g., Cavaleiro 1516; Ramalho 1977-1978; 1988; Sánchez Salor 2002; 2006; 2010).

In spite of Pastrana’s grammar being completely medieval not only in its division in four parts but also in the methodology and in the grammatical terminology (see Fernandes 2019), Sánchez Salor (2010: 204) states that Pastrana was more modern than Cavaleiro and, in some way, even than Elio Antonio de Nebrija (see also Fernandes 2019). Sánchez Salor also considers the Pastrana’s grammar the first renaissance grammar in Portugal and „neither Pastrana is so barbaric as some of his contemporaries want to present him, nor Nebrija is so innovative as he intends to present himself. What underlies largely, in the face of the confrontation, is the interest to impose his own grammar in the schools“ (Sánchez Salor 2010: 194, my translation).

In Portugal there is not any known reedition of Pastrana’s grammar, but it was taught until approximately 1530-1535, and there are other grammar books published in the first decades of the 16th century under Pastrana’s name, viz., by João Vaz (fl. 1501) 4 , until at least 1522 (see Verdelho 1995: 92; Ponce de León 2015: 11-12). After the definitive establishment of the Portuguese University in Coimbra (1537) we have no mention of another grammar published in Portugal based on Grãmatica Pastrane.

![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)

![[arrow up]](http://diglib.hab.de/images/arrowup.png)